English language

Published April 30, 1969

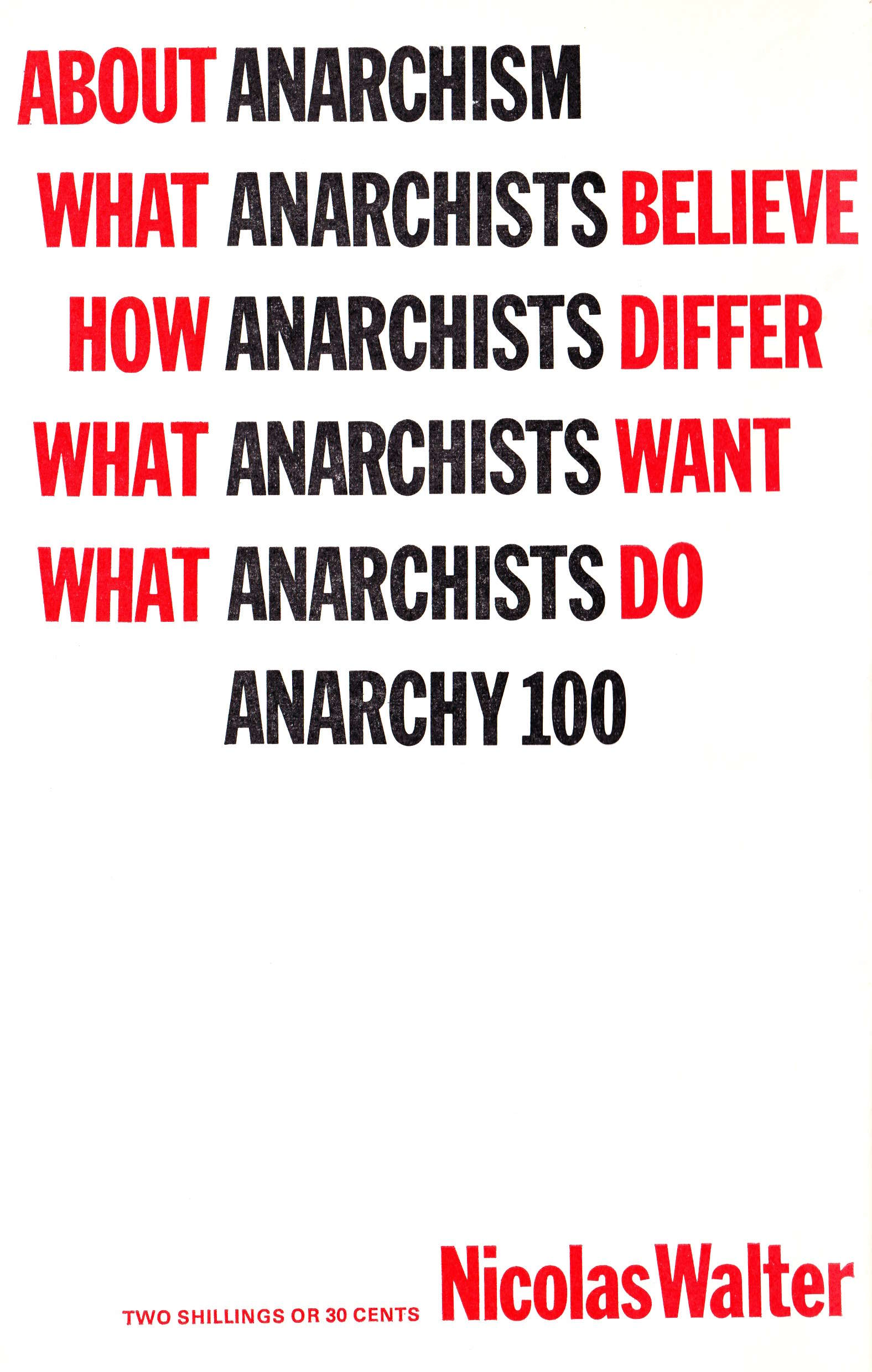

what anarchists believe, how anarchists differ, what anarchists want, what anarchists do

English language

Published April 30, 1969

The modern anarchist movement is now a hundred years old, counting from when the Bakuninists entered the First International, and in this country there has been a continuous anarchist movement for ninety years (the Freedom Press has been going since 1886). Such a past is a source of strength, but it is also a source of weakness—especially in the printed word. The anarchist literature of the past weighs heavily on the present, and makes it hard for us to produce a new literature for the future. And yet, though the works of our predecessors are numerous, most of them are out of print, and the rest are mostly out of date; moreover, the great majority of anarchist works published in English have been translations from other languages.

This means there is little that we can call our own. What follows is an attempt to add to it by making a …

The modern anarchist movement is now a hundred years old, counting from when the Bakuninists entered the First International, and in this country there has been a continuous anarchist movement for ninety years (the Freedom Press has been going since 1886). Such a past is a source of strength, but it is also a source of weakness—especially in the printed word. The anarchist literature of the past weighs heavily on the present, and makes it hard for us to produce a new literature for the future. And yet, though the works of our predecessors are numerous, most of them are out of print, and the rest are mostly out of date; moreover, the great majority of anarchist works published in English have been translations from other languages.

This means there is little that we can call our own. What follows is an attempt to add to it by making a fresh statement of anarchism. It is addressed in particular to readers in Britain at the end of the 1960s—a place and a time in which there is a considerable revival of interest in anarchism as a basis not for sectarian argument about the past but for practical discussion about the future.

Such a statement is necessarily an individual view, for one of the essential features of anarchism is that it relies on individual judgement; but it is intended to take account of the general views prevailing in the anarchist movement and to interpret them without prejudice. It is expressed in simple language and without constant reference to other writers or to past events, so that it can be understood without difficulty and without any previous knowledge. But it is derived from what other people have said in the past, and does not purport to be original. Nor is it meant to be definitive; there is far more to say about anarchism than can be fitted into thirty-two pages, and this summary will no doubt soon be superseded like nearly all those that have preceded it.

Above all, I make no claim to authority, for another essential feature of anarchism is that it rejects the authority of any spokesman. If my readers have no criticism to make, I have failed. What follows is simply a personal account of anarchism drawn from the experience of fifteen years’ reading anarchist literature and discussing anarchist ideas, and of ten years’ taking part in anarchist activities and writing in the anarchist press.